Hairstyle fashion in Rome was ever changing, and particularly in the Roman Imperial Period there were a number of different ways to style hair. As with clothes, there were several hairstyles that were limited to certain people in ancient society. Styles are so distinctive they allow scholars today to create a chronology of Roman portraiture and art; we are able to date pictures of the empresses on coins or identify busts depending on their hairstyles.

Barbery was introduced to Rome by Publius Titinius Menas, who, in 209 or 300 BCE, brought a barber from the Greek colonies in Sicily. During earlier parts of Roman history, most people acted as their own barber. Due to the difficulty in handling the tools of barbery the craft became a profession. This profession prospered most during the Imperial period.

Significance

[edit]

Much like today, hair for the Romans was as much an expression of personal identity as clothes. Hairstyles were determined by a number of factors, namely gender, age, social status, wealth and profession. A woman’s hairstyle expressed her individuality in the ancient Roman World. How one dressed one’s hair was an indication of a person’s status and role in society.

Hair was a very erotic area of the female body for the Romans, and attractiveness of a woman was tied to the presentation of her hair. As a result, it was seen as appropriate for a woman to spend time on her hair in order to create a flattering appearance. Hairdressing and its necessary accompaniment, mirror gazing, were seen as distinctly feminine activities. Lengthy grooming sessions for women were tolerated, despite writers such as Tertullian and Pliny commenting on their abhorrence for time and energy women dedicate to their hair.[1] However, the numerous depictions of women hairdressing and mirror-gazing in tomb reliefs and portraiture is a testament to how much hairdressing was seen as part of the female domain.[2]

For more than just attractiveness, hairstyling was the leisure pursuit of the cultured, elegant woman. Hair was seen as much as an indication of wealth and social status as it was of taste and fashion. But unlike modern-day hairstyles, comfort and naturalism for the Romans took a back-seat to hairstyles that displayed the wearer’s wealth to a maximum. In other words, having a complex and unnatural hairstyle would be preferred to a simple one, because it would illustrate the wealth of the wearer in being able to afford to take the time to style their hair.[3] For women to have a fashionable hairstyle showed they were part of the elegant Roman culture.

A ‘natural’ style was associated with barbarians, who the Romans believed had neither the money nor the culture to create these styles. “Natural” showed a lack of culture, and grooming of the hair went hand-in-hand with being part of a sophisticated civilization. The association with barbarians was why Roman men kept their hair cut short.[3] It was the job of slave hairdressers, called ornatrices, to create their master’s hairstyle new each day, as well as pulling out any grey hairs.[4]

Apart from society, hair was used symbolically to mark rites of passage; for instance, loosened hair was common at a funeral, and the seni crines was the hairstyle worn by brides and Vestal Virgins; divided and plaited into six braids, and in the case of the bride, it was parted with a spear.[5] A bride’s hair was parted with a hasta recurva or hasta caelibaris, a bent iron spearhead and crowned with flowers. In addition to ceremonies hairstyle defined the age of a woman.[6] There was a marked difference in hair acceptable for preadolescent girls and sexually mature women. Preadolescent girls would often have long hair cascading down the back where as women would have equally long hair but it would be controlled through wrapping and braiding.

Medical and religious

[edit]

It was common for sailors to shave their eyebrows and dedicate the hair to the gods, to earn their protection. The Vestal virgins would hang leftover hair on trees as a religious service and to consecrate a person. In Martial’s Epigrams a character named Encolpus dedicates their hair to a character named Phoebus.[7] The Romans also believed that shaving one’s head was necessary for diagnosing certain illnesses. Pliny the Elder suggested many possible cures and remedies for balding hair.[8] It was a popular custom to dedicate the hair from someone’s first haircut to the gods. Usually, the time a Roman would perform this act was when they reached the age of 20 or donned the toga virillis.[9]

Headgear

[edit]

Veils

[edit]

Perhaps due to its erotic association, hair was often linked with Roman ideas of female modesty and honour. We know that veils were important in this case, as they protected against (or encouraged, according to Seneca the Elder) solicitations by men.[10] The palla was the mark of a married, respectable woman. It was a piece of cloth wrapped around the body with one end over the shoulder. There is significant evidence for the palla being draped over the back of the head as a veil.[11]

The palla supposedly signified the dignity and sexual modesty of a married woman, but due to its encumbering nature as a veil, there has been much debate whether it was only worn in public by the aristocracy, or if at all by working women of lower classes.[12] Vittae were woollen fillets that bound a married woman’s hair. They were another indication of a wife’s modesty and purity and were seen as part of the clothing and presentation of a matron.[13] Vittae could be inset with precious stones, or in the case of the Flaminicae, they would be purple in colour.

Wigs

[edit]

Due to the nature of hair and the relatively wet climate in the upper reaches of the Roman Empire, there are very few examples of wigs that survive to this day. Women wore wigs whether they were bald or not. So too did men; Emperor Otho wore a wig, as did Domitian.[14] Wigs allowed women to better achieve the kind of ‘tall’ styles that particularly punctuated the Flavian and Trajanic eras (e.g. the periods of 69–96 and 98–117 AD). So tall were these hairstyles, that ancient writer Juvenal likens them to multi-storey buildings.

So important is the business of beautification; so numerous are the tiers and storeys piled one upon another on her head!

— Juvenal, Satires[15]

Wigs were made from human hair; blonde hair from Germany and black from India were particularly prized, especially if the hair came from the head of a person from a conquered civilisation.[16] The blond hair of various Germanic peoples symbolized the spoils of war. In cases where wigs were used to hide baldness, a natural look was preferred, therefore a wig with a hair colour similar to the wearer’s original was worn. But in instances where a wig was worn for the purpose of showing off, naturalism did not play much of a part. Obviously fake wigs were preferred, sometimes intertwined with two contrasting hair colours with blonde hair from Germany and black from India.[17] Gold dust also gave the appearance of blond hair and enhanced already blond hair. Emperor Lucius Verus (r. 161 – 169 AD), who had natural blond hair, was said to sprinkle gold dust on his head to make himself even blonder.[18]

A convenience of wigs used by Romans is that they could be directly pinned onto the head of the wearer, meaning a style could be achieved much faster than if it had been done with the wearer’s own hair. Further, it would lessen the inconvenience of having to grow one’s own hair too long. It has been suggested that the necessary length to be able to create these hairstyles daily would be well below the shoulder, perhaps to the waist.[19]

There were two types of wig in Roman times: the full wig, called the capillamentum, and the half wig, called the galerus.[20] The galerus could be in the form of a fillet of woolen hair used as padding to build an elaborate style, or as a toupee on the back or front of the head. Toupees were attached by pins, or by sewing it onto a piece of leather and attaching it as a wig. Further, glue could be used to affix it to the scalp or alternatively, as a bust from the British Museum illustrates, the toupee could be braided into the existing hair.[21]

Janet Stephens is an amateur archaeologist and hairdresser who has reconstructed some of the hairstyles of ancient Rome, attempting to prove that they were not done with wigs, as commonly believed, but with the person’s own hair.[22][23]

Detachable marble wigs

[edit]

Busts themselves could have detachable wigs. There have been many suggestions as to why some busts have been created with detachable wigs and some without. Perhaps the main reason was to keep the bust looking up-to-date. It would have been too expensive to commission a new bust every time hair fashion changed, so a mix-and-match bust would have been preferable for women with less money.[24] Perhaps another reason was to accommodate the Syrian ritual of anointing the skull of the bust with oil.[24]

Or further, in cases where the bust was a funerary commission, it can be safely assumed that the subject of the bust would not have had an opportunity to sit for another portrait after their death.[25] Although exactly how these marble wigs were attached is unknown, the likely difficulty of changing the ‘wigs’ effectively would have probably put many women off choosing a detachable and reattachable bust in the first place.[26]

Profession

[edit]

Dyes

[edit]

Dyeing hair was popular among women, although frequent dyeing often made it weaker. Tertullian discusses a hair dye that burnt the scalp and was harmful for the head.[27] Artificial colors were applied as powders and gels. Henna or animal fat could be applied to make the hair more manageable.[28] To prevent graying, some Romans wore a paste at night made from herbs and earthworms; in addition, pigeon dung was used to lighten hair. In order to dye hair black, Pliny the Elder suggests applying leeches that have rotted in red wine for 40 days.[29]

Dyeing hair red involved a mixture of animal fat and beechwood ashes[30] whilst saffron was used for golden tones.[31] Ovid mentions several vegetable dyes.[32] To cure diseases such as hair loss, Pliny suggests the application of a sow’s gall bladder, mixed with bull’s urine, or the ashes of an ass’s genitals, or other mixtures such as the ashes of a deer’s antlers mixed with wine. Further, goat’s milk or goat’s dung is said to cure head lice.[33]

Suetonius, in his The Twelve Caesars states:[34]

These he reserved for his parade, compelling them not only to dye their hair red and to let it grow long,

— Suetonius, The Twelve Caesars

Roman prostitutes dyed their hair yellow to indicate their profession. Usually, they would just wear a wig dyed yellow. To dye their hair yellow they used a mixture of the ashes of burnt nuts or plants. Romans would make a black dye by fermenting leeches in a lead vessel.[35]

Curling irons, pins and hairnets

[edit]

The calamistrum was the name for the Roman curling iron. It consisted of a hollow metal outer cylinder and a smaller solid cylinder inside it. The hair would be wrapped around the solid cylinder and inserted into the metal outer. The metal outer would be heated in a fire, making the hair curly. It has been reported that because of the frequency and temperature that hair was curled at, thinning and damaged hair was common amongst women.[36]

While gel and henna, as mentioned above, were used to manage hair, hairnets and pins were in common usage too. Poorer women would have used wooden pins, while the aristocracy used gold, ivory, crystal, silver or painted bone. The pins were decorated with carvings of the gods, or beads and pendants.[37]

Society

[edit]

Most barber shops were located in tabernae. Many shops clustered around the Temple of Flora and the Circus Maximus.[38] It is possible that only barbers with connections to wealthy people were allowed or able to practice in tabernae, while most others would have been forced to practice in the open. They would be identified of signs depicting scissors or mirrors located outside the shop’s premises. Plautus, an ancient Roman playwright, wrote about characters going to the barber’s shop. Whilst there, they would often discuss gossip and talk about news.[39] This resulted in Roman barbers gaining a habit of excessively talking about the latest news and gossip to their customers. Oftentimes barber’s shops became incredibly crowded. Emperor Domitian regulated barbershops, prohibiting razors from being drawn in the middle of a dense crowd, and barbers from practicing in public places. Another emperor, Trajan, once pondered how the Lex Aquilia, a law concerning liability, would conflict with this law. Trajan cited an example of a slave who had their throat slit by a barber because the barber, who was practicing in a public space, had their hand moved by a ball. There were also barber labor unions.[9][40]

Process

[edit]

To begin the haircut the customer would step on a low stool. Then the barber would place a wrapper around them in order to protect their toga. He would proceed to comb through the customer’s hair while asking them what he should do with their hair. Most Romans liked their hairs to be of even length.[40] Sometimes the head or eyebrows were even shaved.[41] Aside from cutting hair Roman barbers would also clean and pare the nails of their customer using special knives.[40] The corns were also cut, stray hairs plucked, and warts removed.[40] Shears were used to cut the hair on the crown of the head. At the end of the barber’s work they would place a mirror up to the customer’s face so that they could judge the quality of their work.[41] The barber would also use a curling iron, tweezers, and razors.[41] Each razor had its own case.[42] Some barbers made enough money to own 20 slaves and 20 horses.[40]

Styles over time

[edit]

Roman hairstyles changed, but there were several constant hairstyles that were used continuously, such as the tutulus, or the bun. The beehive, helmet, hairbouquet or pillbox are modern day names given to Roman hairstyles.

Tutulus

[edit]

The tutulus was originally an Etruscan style worn commonly in the late 6th and early 5th century BCE[43] was a hairstyle worn primarily by the materfamilias, the mother of the family.[44] It remained in constant use even when fashion changed. To achieve it, the hair was divided and piled high and shaped into a bun, after which it was tied with purple fillets of wool. By the end, the hair would be conical in shape. It was also the hairstyle worn by the flaminicae.[44]

Republican period and Augustan era styles

[edit]

The nodus style was particularly common in the Republican period. In Imperial iconography the nodus coiffure was associated predominately with the women of Augustus’ household. The nodus style saw the hair parted in three, with the hair from the sides of the head tied in a bun at the back while the middle section is looped back on itself, creating an effect not unlike the (comparably modern) Pompadour style.[45] Livia, wife of Augustus, and Octavia, sister of Augustus, particularly favoured the nodus style, both continuing to use it well into the Imperial Period.[46]

Other styles in the Julio-Claudian era were designed to be simple, with hair parted in two and tied in a bun at the back. This was perhaps done in order to juxtapose Roman modesty against Cleopatra and her flamboyance.[47]

Flavian and Antonine hairstyles

[edit]

Flavian and Antonine hairstyles differed greatly between men and women in real life and in the physical appearance of hair for male and female sculptures. In ancient Rome hair was a major determinant of a woman’s physical attractiveness; women preferred to be presented as young, and beautiful. Therefore, female sculptures were known to have dramatic curls carved with strong chiaroscuro effects. On the other hand, most men in the Flavian period of the late first century CE have their hair trimmed short on the crown like the portrait of Domitian for example (pictured) that implied an active role in society, while a woman’s connoted passivity.

Flavian and Antonine hairstyles are perhaps the most famous, and extravagant, of Imperial Rome’s styles. During this time the aristocratic women’s style became the most flamboyant (Cypriote curls). The styles were lofty, with masses of shaped curls and braids. The high arching crowns on the front were made using fillets of wool and toupees, and could be attached to the back of the head as well as the front. Typically, as in the case of the famous Fonseca Bust (pictured), this particular hairstyle appears to have been popular during the Flavian period. The hair was combed into two parts; the front section was combed forwards and built with curls, while the back was plaited and coiled into an elaborate bun (orbis comarum).[48] This fashion was described by the writer Juvenal as the hairstyles that made women appear tall from the front but quite the opposite from the back.

The later Antonine period saw curls at the front of the head brought to a lower level than the Flavian period. The braids coiled at the back of the head were brought further forward, instead often resting on the top of the head. Another style of the Antonine period saw the hair separated into rivets and tied at the back.[49]

Furthermore, whether Roman portraits faithfully translate the actual hairstyles worn by the sitters is problematic because of the scarcity of surviving hair which leaves little basis of comparison. The second problem is the physical accuracy of the Roman portraits itself. However, as a result of the many sculptures that have some reference to hair, ethnographers and anthropologists have recognized hair to play a key role in identifying gender and determining societies in which individuals belonged.[49][50]

Severan dynasty

[edit]

Julia Domna, wife of Septimius Severus, had a particularly notable hairstyle. Julia Domna was the wig’s most influential patron. She wore a heavy, globular wig with simple finger-sized waves with a simple center parting. Julia Domna was the daughter of a high-ranking priest from Syria, and it has been suggested that her style was indicative of her foreign origins.[51] Despite being from the East, she adopted a wig to project a familiar Roman guise and particularly in order to imitate her predecessor, Faustina the Younger.[52] In 2012 Janet Stephens‘s video Julia Domna: Forensic Hairdressing, a recreation of a later hairstyle of the Roman empress, was presented at the Archaeological Institute of America’s annual meeting in Philadelphia. Foreign women often wore their hair differently from Roman women, and women from Palmyra typically wore their hair waved in a simple center-parting, accompanied by diadems and turbans according to local customs. Women from the East were not known to commonly wear wigs, preferring to create elaborate hairstyles from their own hair instead.[52] As time progressed, Severan hairstyles switched from the finger-waved center parting style, to one with more curls and ringlets at the front and back of the head, often accompanied by a wig.[53]

Men’s hairstyles

[edit]

Roman hairstyles for men would change throughout ancient times. While men’s hair may have required no less daily attention than women’s, the styling as well as the social response it engendered were radically different. Lengthy grooming sessions for men were looked at as taboo. For example, the emperor Augustus employed two to three barbers to simultaneously trim his hair, in order to speed up the process.[54] Women’s hair was carved according to different techniques based on the sex. For example, one of the primary features that is seen in many women but never in men is long hair divided by a center part. It is apparent men never wore this, since there is no biological difference in hair growth between sexes; how hair is parted is a practice determined solely by culture. Eyebrows of both sexes were tended to be treated in the same manner.[55]

During the days of the Roman Kingdom and Early Republic, it is most likely Roman men wore their hair long with beards, in the style of Greeks. With the introduction of barbers called tonsors in about 300 BC it became customary to wear hair short. In Ancient Rome, household slaves would perform hairdressing functions for wealthy men. However, men who lacked access to private hairdressing and shaving services or those who preferred a more social atmosphere went to a barbershop (tonstrina). Barbershops were places of social gatherings and a young man’s first shave was often even celebrated as a passage to manhood in the community. The barbers usually shaved the customers faces with iron razors and applied an aftershave with ointments that may have contained spider webs.

Among the Patrician class and Equites, a clean shave and a closely trimmed head of hair would become the rule in Rome beginning in the second century BC. Shaving one’s beard became popularized and then normalized by General Scipio Africanus and his legions during the time of the Second Punic War. Scipio both sought to emulate the style of Alexander the Great, who shaved to prevent enemy soldiers from grabbing his beard in battle,[56] as well as to signal to the conservative Roman senate that new ways of thinking were needed to defeat Hannibal.[57] Among those Roman men who wished to keep some facial hair, it was acceptable to shave one’s mustache but not the remainder of one’s face, a style then popular in Greece and seen as Hellenic.[58] Roman men who wore beards would not be admitted into the senate unless they shaved.[59]

Despite rigid class expectations, there were exceptions to social custom when it came to men’s hairstyles. For example, beards were permitted if the wearer was in mourning. Numismatic evidence demonstrates Emperors and other prominent figures wearing beards during periods following the death of a close family member or military defeat.[56] A notable exception to trimmed hair in the early Imperial period was the Emperor Tiberius, who wore his hair longer in the back than on the front or sides of his hair, so that it covered the nape of his neck. The historian Suetonius notes this as a family tradition of the men of the Claudian family. The Claudians were one of the oldest families in Rome, and could trace their lineage back to the first days of the Republic, when longer hair was in style and favored especially by the Patrician class.[60] Tiberius’ successor, his great-nephew Caligula, carried on this hairstyle, even after he had begun to go bald, as did other male members of Tiberius’ family.[61]

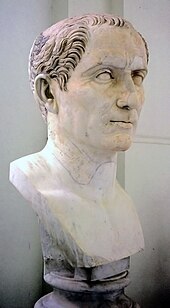

In Ancient Rome it was desirable for men to have a full head of hair. This was a problem for Julius Caesar. Being bald was considered a deformity at the time, so Caesar went to great pains to hide his thinning hair, combing his thin locks forward over the crown of his head. Suetonius wrote: “His baldness was something that greatly bothered him.” Caesar was allowed by the Senate to wear a laurel crown with which he was able to mask his receding hairline.

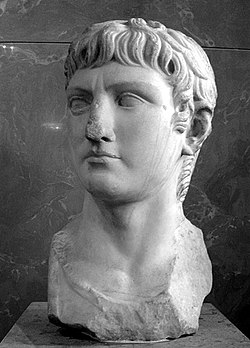

During the Roman times it is easy to know how the emperors wore their hair. For example, one constant feature of Augustus‘s portraits is his hairstyle, with its distinctive forked locks of hair on his forehead.[62] The emperor was most often looked at as the trendsetter during these times. This is shown by the emperor Nero (54–68 AD), who adopted elaborate hairstyles with curls and was the first Emperor to have facial hair, specifically a neckbeard.[63][64] In imitation of Nero, men began to curl their hair, although there is no evidence they began wearing beards in his style. Following Nero, in the Flavian period, most men had hair trimmed short on the crown and lacking strong plasticity.[55] During the next few decades a straight hair cut with forehead bangs was popular with Trajanic men.

Following Trajan, his adopted heir Hadrian (117–138 AD) became the first emperor to wear a full beard, kicking off a trend among emperors. Every emperor for the next 100 years wore a full beard, with the exception of Caracalla‘s co-regent Geta, who only ruled for 11 months alongside his brother and was murdered at 22.[65] Hadrian’s decision to grow a beard has usually been seen as a mark of his devotion to Greece and Greek culture. One literary source, the Historia Augusta, claims that Hadrian wore a beard to hide blemishes on his face, although most historians consider the book’s reliability dubious.[66]